There are a stories of convicts aplenty, many of whom are marked down for literature for their extraordinary traits. It could be their tough-minded recalcitrance, their hard-bitten experience (often gained at the hands of merciless superiors). It might be their natural resilience to pain or their never-say-die derring-do.

WITH ADAM COURTENAY

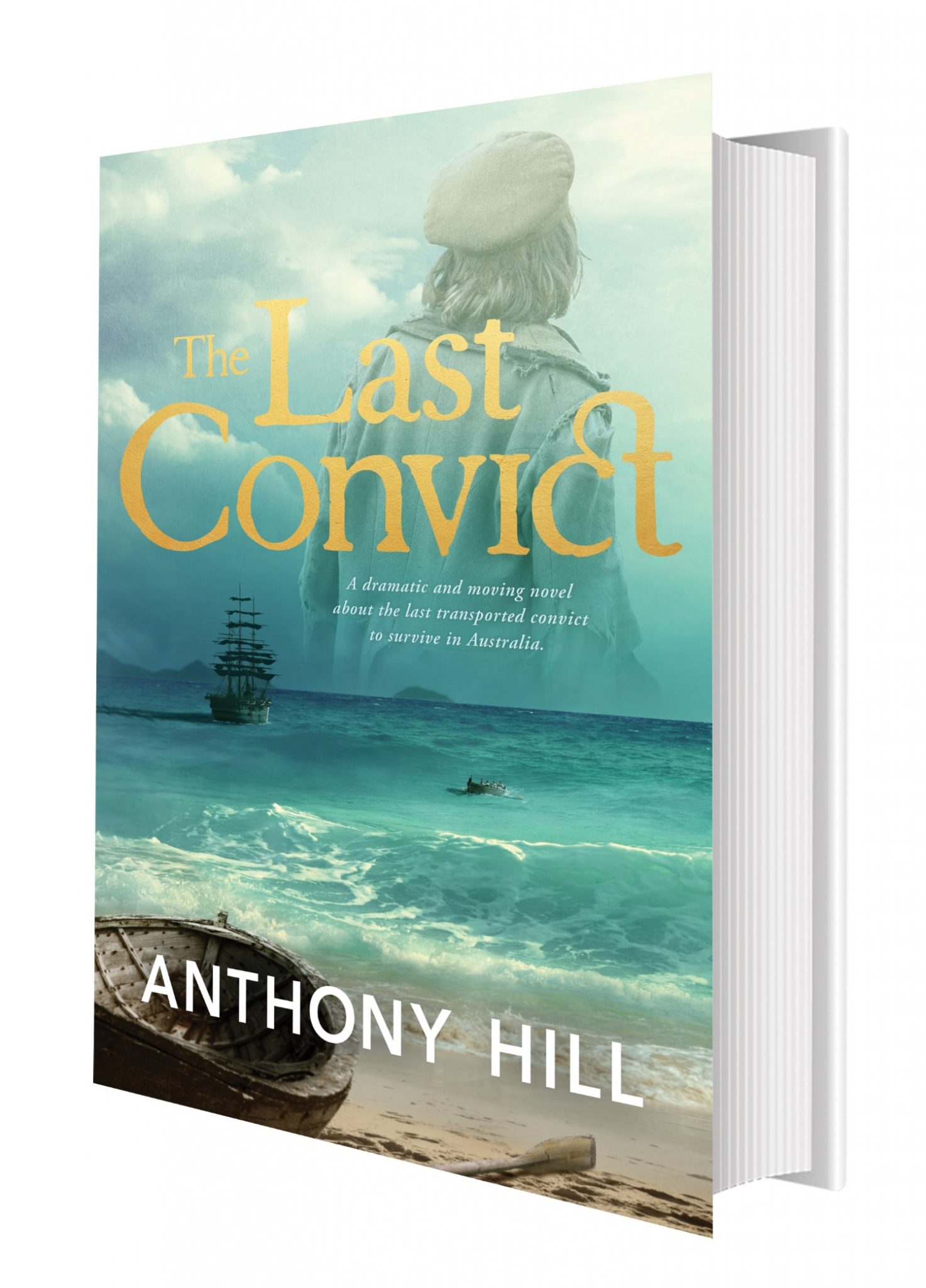

The Last Convict By Anthony Hill / Michael Joseph, 368pp, $32.99

Samuel Speed, the subject of Anthony Hill’s The Last Convict, has none of those irredeemable features that we love to prize in the genre. He is the John Doe of the convict world.

He was the convict who came late when the system was less savage. He did porridge and kept his head down. Speed’s only real claim to fame was his survivability: he lived well into his 90s and was the last living convict in Australia.

According to his convict indent, he was 20 when he was transported for setting fire to a hayrick in 1863. He was 5 foot 3 tall, with dark grey hair, hazel eyes, and had a cataract on his left eye. He was able to read and write.

He was released as a bondsman three years later, and in 1871, at the end of his sentence, became an expiree. He died at the Perth Old Men’s Home on November 8, 1938.

Hill’s book is part fact and fiction and he melds them together extremely well. Other than the record, he has only a few sources to go from: the chief one being an interview Speed gave with the Perth daily, The Mirror, two months before his death.

Hill creates an interesting interplay between the fictional journalist Joshua Cribben and Speed. Cribben thinks he might uncover the scoop of the year.

Perhaps Speed may know something about the great escapes from the Swan River settlement that hitherto have not been uncovered.

The ageing Speed, unable to talk for long periods, knows all about his more famous peers, but adds nothing to the knowledge base.

What the journalist of 1938 wants, is exactly what we want: the great stories that have been missed, the excellent detail.

He asks about the escape of six Irish Fenians from the Convict Establishment (afterwards Fremantle Prison), known as he Catalpa Rescue. He wants to know all about the convict turned bushranger Moondyne Joe. Hill uses Sam to tell the Swan River convict story very well, but minus any new or juicy bits.

As the actual Mirror story relates: “ … old Sam’s memory is clouded with time, and there is none to stir it for him. He was never a member of a chain gang; carries no lash marks on his back as other unfortunates did; remembers Garden Island when it was known as Sulphur Town; helped build the old Fremantle bridge; has never smoked in his life.’’

“Never cared for it,” Sam told the paper. “Besides, I could always sell my tobacco rations to the other prisoners.”

And yet the disappointed journalist is somehow transfixed by Speed’s normality. There he is in the flesh, the last survivor of a bygone age, a Victorian criminal still standing as a first-hand witness to the colony’s sinful past.

Sam regrets not having a wife and kids – but then his dicky knee might have put him (and them) in the poorhouse, so no real regrets there. Maybe, he says, he should have gone east with his mate Tommy to find a giant nugget of gold? But no, says Sam, the dicky knee would have stopped that too.

This is good historical fiction precisely because Hill creates a highly valid character and never transgresses the bounds of reality. Sam has a few early career ruses up his sleeve, but they are about conning some of the clergymen to give him books.

He doesn’t want spirits, tobacco or a key – just books. He pretends to be pious so that he can read Dickens. It works.

In the character of Speed, Hill shows another truth. That having been so inculcated into the prison life so early, released men lost the ability to cope with the vicissitudes of freedom.

Speed is so fully institutionalised by the system being run by the state. The old men’s home is just like prison, with a bit more freedom and few more comforts. He happily runs his own life by its routines, just as he did in Fremantle Prison.

Old Sam is content with what he now had, having known of nothing much else. “He’s as lively as a two-year-old,” said one of the attendants. “We just prepare his bath and he jumps in and out as nimbly as if he were getting ready to go courting again.”

This is not the average convict story, which seeks to shock and amaze with lurid tales of cruelty, escape and savagery. But it is the story of the average convict, which makes the story a little bit extraordinary.

Adam Courtenay’s most recent book is The Ghost and the Bounty Hunter.

This article appeared in the Autumn 2021 edition of Life Begins At… Click here to read or here to subscribe and never miss an issue!

Add Comment