Postcards were the emails of the late 19th and early 20th century. Snippets of holidays, news of war and news of peacetime. In this extract from his recent book, historian Jim Davidson sifts through the cards to give us a snapshot into the golden age of post.

Postcards represent the popularisation of photography, extending far beyond those who could afford a camera. By the 1890s, they were being described as “the plague of Germany”. Postmen were seen going from table to table on the terraces of restaurants, selling cards and stamps so that people could buy a card on impulse, and post it in the small box placed, like a knapsack, on the postman’s back. Later, in England, automatic postcard vending machines were placed in railway stations. People had taken to postal cards and postcards immediately, right from the release of the first one in Austria. Their cheapness and utility (and the cheaper postal rate), to say nothing of the greater literacy throughout society, meant that they caught the tide of modernity. But not everybody was in favour of them. They gave no privacy — attempts made by some to preserve it by writing messages upside down were laughable, given the prying eyes of servants. They were brief, intrusive, vulgar: “There is no room for anything polite” ran the objection. But this was the minority opinion.

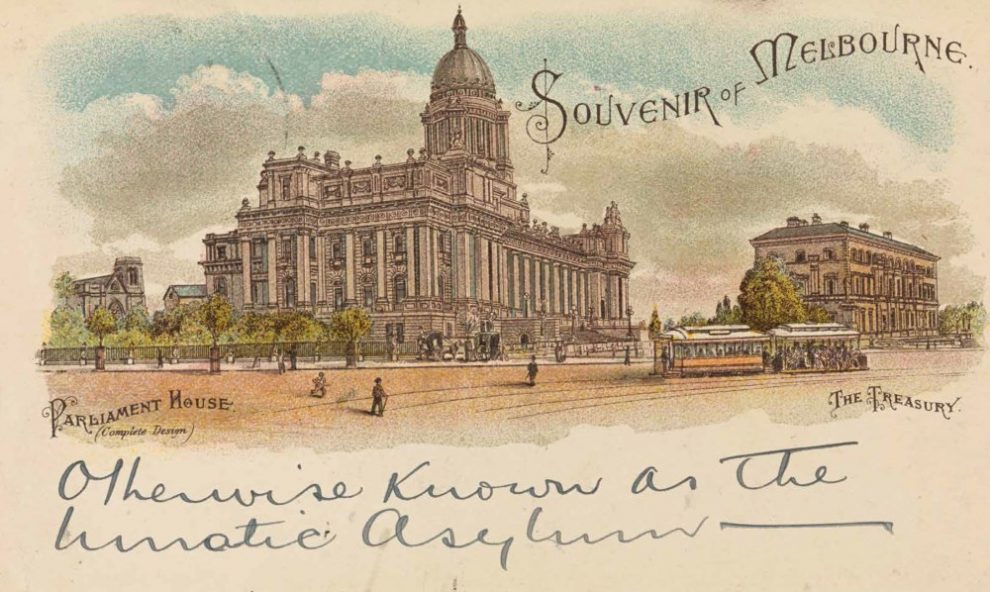

Even so, members of the Legislative Council used it as an argument to delay the introduction of postal cards in Victoria. In the 1890s, Britain had some catching up to do. Postcards were still the smaller size of the “court card” until 1899, when the Post Office permitted the larger, Continental size. This was important as people still had to write the message on the same side as the illustration. The illustrations, though, tended to expand in size — as our Australian examples show. So the British found a solution: the “divided back”, the line drawn on the plain side of the card, allowing address and message to sit side-by-side. These changes released a deluge. In 1909, the Post Office sold 833 million stamps for postcards — nearly 20 for every single person in the UK.

In fact, the actual number of postcards sold is incalculable, as a great number were bought as souvenirs and put straight into albums. It had long been practice to sort the mail on trains, so that when the Sydney train arrived in Melbourne, tagged bags were lined up for the next stage of delivery. In 1910, central Sydney had three mail deliveries a day: a royal commission suggested that these should be augmented to match Melbourne’s four!

Given that telephones were still rare, to describe postcards as the emails of the day is no exaggeration. Many more people used postcards than collected them. Businesses advised clients of new stock, travelling salesman of an impending visit, and everybody used them to suggest meeting. Sometimes people sent them saying they would write later (or hadn’t heard from the addressee); they were also ideal for the unequal exchange between mothers and sons. For a time postcards were so popular that they almost swallowed up birthday and Christmas cards. They might also be useful, as other cards have been, when people were tentative about expressing their feelings.

Jim, a serving soldier, sent a girl “A kiss from France”, a delicate silk card, hoping that “you won’t think me too rude”. Unlike stamps, postcards were collected more frequently by women than by men — but not markedly so. Male interest was certainly pronounced in military cards — commonly of a ceremonial kind — sporting cards, and those of bridges, mines, and industry. Both sexes responded to cards expressing patriotism — in overdrive then, as it was the period of both the greatest pride in the British Empire, and the optimistic beginnings of newly federated Australia.

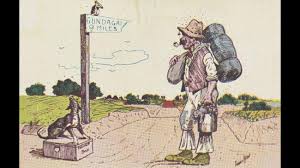

In England, rather more than here, the positioning of a stamp — upside down, or sideways, and other inventive variations — could indicate whether they wished to encourage a suitor, or not. It has been estimated that, worldwide, perhaps up to 90 per cent of all postcards were topographical, depicting places. Australian topographical cards were also in demand from curious people overseas, so people to exchange with were readily found. In Britain, and to a much more limited extent in Australia, there were postcard magazines with lists of addresses. They were effective: “Sorry I cannot exchange,” wrote MF in Adelaide to somebody in Muswell Hill, London, explaining that “(I) already have too many correspondents”. The postcards Australians sent to one another were also, more often than not, manufactured overseas.

In 1902, the Sydney GPO handled 1,734,340 postcards; by 1906, the total had shot up to 12,621,096. This was a sevenfold increase, whereas letters handled over the same period increased by only one third. There may have been, in the peak year 1908, as many as 40 million non-official postcards mailed in Australia.

A sharp real photographic card is today prized by the collector, not least for its maverick quality. For “real photos” could be superbly taken, captioned and produced by professional photographers; by cameramen working in the street; or increasingly, as the camera became all pervasive, by enthusiastic amateurs who printed their photos to postcard size.

The postcard boom had already passed its peak when, in 1911, new postal regulations effected a common charge of one penny for letters and postcards alike. Postcards now lost their competitive advantage. Further decline was stanched to some extent by World War I, since patriotic exhortation gave the industry a second wind. But once the war ceased, there was a new landscape.

Postcards were now seen as old-fashioned, a fad from the other side of the war’s great divide. In a world that had seen the spread of the aeroplane, a wider use of telephones, and which soon would know public radio, they no longer had the cachet of modernity. In reaction to the horrors of the war, the prevailing mood of the 1920s was one of exuberance. The portable camera came into its own: the “snap” (snapshot) was prized now, not the formal, rather static compositions favoured by the Edwardians. Friends and family were increasingly the focus in people’s albums: if inserted at all, postcards were the intruders. The rise of local companies in Australia obscured this decline for a time. But the golden age of postcards, from 1900 to 1920, was beyond revival. Collectors have, in response, extended the “silver” age, from the interwar period to the 1950s and now to the 1970s.

Meanwhile, the contemporary popular postcard — no longer doubling as a souvenir which might be kept by the purchaser — has become more and more lurid. It is no longer a statement of modernity, but an iridescent object clamouring for attention, even as it lingers in a diminishing number of racks.

If after World War I there was a decline in printing, so after World War II there was some decline in imagery. Composition could be careless. Then came Kodachrome and the coloured slide. People still sent postcards, but the big thing in the 1950s and early ’60s was the slide night, when the returning couple would inflict their projected photographs on their friends. The topographical postcard was already dying, like the Christmas card, when the internet got into its stride.

Now people can transmit their own photos instantly; quality is immaterial. But a card, apart from the possibility of elegance, has karma: it has wended its way to you from a distant loved one, making the journey in reverse. Should it disappear, something will be lost. Yet the postcard refuses to die completely.

American academics have begun talking of “postcard studies”. In the past, those who approached postcards via fine arts often tended to see them as degraded images. In addition, the sheer number of postcards told against them: they could be dismissed as “cultural detritus”. Now they are being seen as cultural artefacts, as a way into the Edwardian world and a greater understanding of how it functioned.

Moments In Time: A Book of Australian Postcards, by Jim Davidson $RRP $44.99

Add Comment